Elizabeth Sewall Alcott: The Quiet Soul Behind Beth March

The name Elizabeth Sewall Alcott may not appear in textbooks as prominently as her famous sister Louisa May Alcott, but her impact on American literature is profound and quietly powerful. Elizabeth was not a public figure, nor a published writer, but her life story gave depth and emotion to one of the most beloved literary characters of all time—Beth March from Little Women. Through her gentle spirit, quiet courage, and deeply compassionate nature, Elizabeth left a legacy that continues to touch readers across generations.

Born into a Family of Thought and Reform

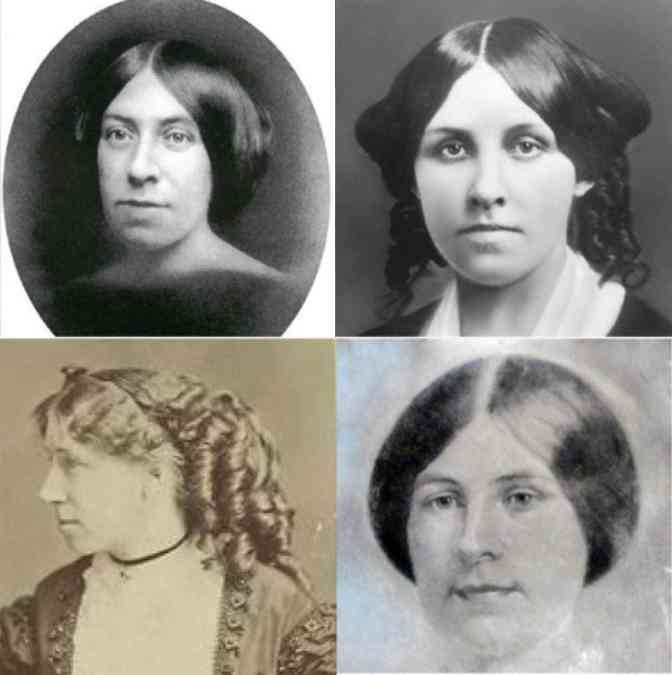

Elizabeth Sewall Alcott was born on June 24, 1835, in Boston, Massachusetts, into a household built on intellectual pursuit and social activism. She was the third of four daughters born to Amos Bronson Alcott, a transcendentalist philosopher and educator, and Abigail May Alcott, one of the first paid social workers in Massachusetts. Her siblings included Anna Bronson Alcott, Louisa May Alcott, and Abigail May “May” Alcott, each of whom would go on to leave their own mark in the literary and artistic world.

Initially named Elizabeth Peabody Alcott, after her father’s colleague and close friend, her middle name was later changed to Sewall after a falling out between Bronson and Peabody. The new name honored her maternal grandmother, Dorothy Sewall May, and symbolically tied her more closely to the May family’s lineage of strength and quiet dignity.

Quiet by Nature, Gentle by Heart

Elizabeth, known affectionately as “Lizzie,” was known from a young age for her reserved demeanor, selfless nature, and introspective personality. Unlike her sister Louisa, who brimmed with ambition and imagination, Lizzie preferred the calm of home life. She was especially fond of music and found joy in playing the piano. Family letters and journals reveal that she had an innate sweetness, never demanding attention, yet always deeply loved.

Her physical appearance is often described in family writings as petite and delicate, with soft eyes and a quiet smile. Although no exact height is recorded, her frail health and gentle disposition painted the picture of someone whose presence was calming and graceful.

A Life of Simple Devotion

Lizzie’s daily life was spent in the rhythms of a household that prized contemplation, morality, and care for others. Though her family faced frequent poverty and uncertainty—often relying on the charity of friends like Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau—Lizzie never complained. She embraced her duties with warmth and grace, often tending to her younger sister May or helping her mother in the home.

It was in 1856 that Lizzie made a decision that would unknowingly seal her fate. A poor German immigrant family in Concord had fallen ill with scarlet fever, and Lizzie, ever the compassionate soul, stepped in to help them. In doing so, she contracted the disease herself. Though she initially recovered, the illness weakened her immune system significantly, and she never fully regained her strength.

The Long Decline and Heartbreaking Goodbye

Over the next two years, Lizzie’s health gradually deteriorated. Despite the family’s best efforts—medicinal treatments, rest, and the emotional support of her sisters—her body began to give way. The emotional weight of her decline was especially heavy for Louisa, who had always been close to her and who took to writing and journaling as a means of coping.

In early 1858, Lizzie stopped eating. The family understood she was preparing herself for death. On March 14, 1858, she passed away peacefully at the age of 22, surrounded by her family. Her death left an unfillable void in the Alcott home. She was buried in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Concord, Massachusetts, in what is now known as Author’s Ridge, not far from where Emerson and Thoreau would also be laid to rest.

Her net worth, like most women of her time—especially those who didn’t pursue careers—was essentially nonexistent in material terms. But in spiritual wealth and emotional value, she was immeasurably rich.

Beth March: A Tribute in Fiction

Two years after Lizzie’s death, Louisa began to draft the novel that would immortalize her sister. Little Women, published in 1868, introduced readers to four sisters—Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy—each modeled after the real Alcott daughters. The character of Beth March was an unmistakable tribute to Lizzie.

Beth was portrayed as quiet, selfless, musical, and morally pure—a reflection of everything Elizabeth embodied. The scene where Beth contracts scarlet fever, grows weaker, and eventually dies is drawn directly from Louisa’s memory of Lizzie’s illness. These chapters have made generations of readers weep, not simply because of Beth’s death, but because of how real and tender her presence feels on the page.

Louisa later wrote that portraying Beth was one of the most difficult emotional tasks she had ever undertaken. Writing Beth’s death was, in many ways, her final goodbye to Elizabeth. But it was also a way to preserve her memory, giving Lizzie the recognition her life had quietly earned.

Why Elizabeth Still Matters Today

Elizabeth Sewall Alcott’s influence didn’t end with Little Women. She has come to symbolize the virtue of quiet strength—a reminder that some lives, though not loud or long, are deeply meaningful. In a world that often celebrates only the bold, Elizabeth stands as a testament to those who live gently and give fully without asking for anything in return.

Her life philosophy, though unspoken, radiates from the pages of the novel she helped inspire: cherish your family, live with kindness, and accept fate with grace.

Recognition in Modern Times

In recent years, more writers and historians have begun to re-explore Elizabeth’s life, not just through Louisa’s lens but as a person in her own right. Susan Bailey, an Alcott historian, is currently working on The Littlest Woman: The Life and Legacy of Lizzie Alcott, a biography that seeks to draw Elizabeth out from the shadows and give her the individual voice she deserves. The book is still in progress, and an official publication date has not yet been announced.

The Orchard House, the Alcott family home in Concord, is now a museum that draws thousands of visitors each year. Lizzie’s presence is still felt there, from the small piano she once played to the quiet rooms she once walked through.

She had no social media, no fame, no public platform—but her story has traveled across centuries, because it resonates on a human level. Her influence was never loud—it was lasting.

Conclusion

Elizabeth Sewall Alcott lived in a time when women’s lives were often overlooked unless they were publicly accomplished. Yet she left an emotional blueprint that would shape one of the greatest novels in American history. Through Beth March, millions have met Elizabeth, mourned with her family, and admired the quiet courage of a girl who gave everything without ever asking for recognition.

Discover the real heart behind Beth March, read her story.